The term ‘immersive’ is being increasingly used to describe virtual environments and virtual reality; we read about immersive technologies, immersive learning environments and immersive worlds, for example. But what does this actually mean, and do we all experience a sense of immersion in the same way?

These questions have been the subject of research for at least 20 years. One of the seminal works looking at the relationship between the sense of presence we experience in virtual environments and our personal tendencies to become immersed was by Witmer & Singer (1998), who developed the first measurement instrument to estimate individual immersive tendencies. Since then there have been many modifications to, and discussions around, these instruments, but the basic premise remains the same; that we all have different personal tendencies to experience a psychological state of immersion as a consequence of focusing our energy and attention on a coherent set of stimuli, including reading books, watching films and playing computer games. This is now recognised as the construct of ‘immersive tendency’.

So what? Well, it seems that immersive tendency is not only related to the sense of presence we feel in virtual environments, but might also influence how we learn from them. For example, Janssen et al (2016) found a probable relationship between immersive tendency and the effectiveness of a virtual environment for learning, and Falconer (2013) found that a sense of presence, closely connected to immersive tendency, was one of the positive factors affecting student learning in an accident investigation role-play exercise in a virtual world.

In the Virtual Avebury (VA) project, we are interested to see if the responses we received from participants who experienced the simulation might be associated with their immersive tendencies. Practically, we couldn’t ask our participants to fill out a complete immersive tendencies questionnaire, but we did ask a question that estimates two of the features of immersive tendency, i.e. how much they lose themselves in a book or film, and how long the effect lasts. Early analysis of this data has brought up some interesting points, so I thought I’d briefly share those here.

Gender differences?

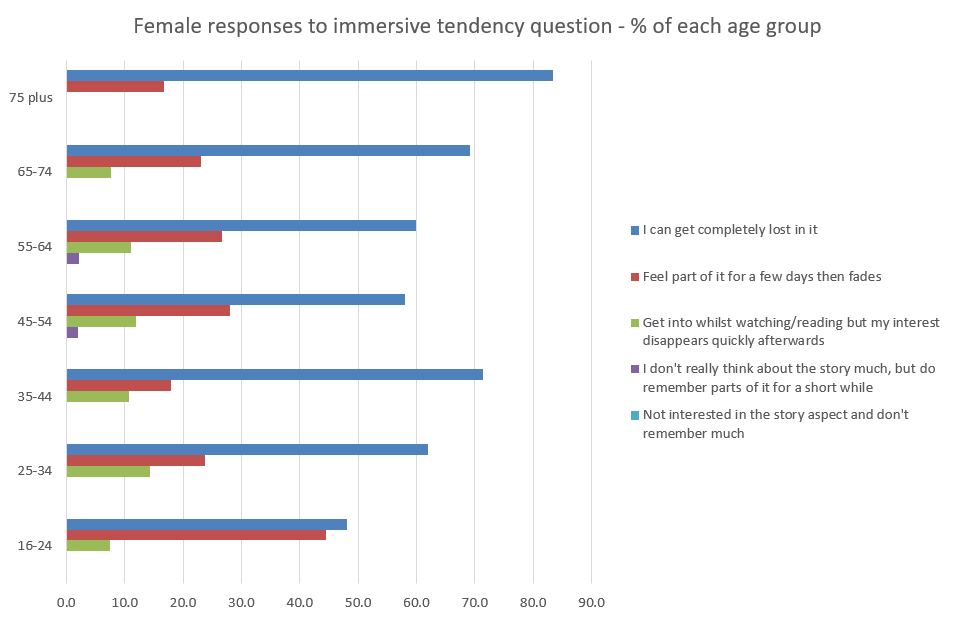

Looking at the 2 graphs in Figures 1 and 2 below, the difference in responses between males and females is clear. The female responses were fairly consistent across the age groups, and also showed a consistent shift towards the more immersive end of the spectrum. The male responses, on the other hand, showed less consistency across the age groups and a greater variance that was centred on a generally lower immersive tendency.

So, if we hypothesise that immersive tendency has a positive effect on responses to virtual environments, we might expect that:

- the responses of females to statements about their reactions to VA would tend to be more closely correlated with their immersive tendency responses than male respondents, and

- females would respond to statements about their experiences more positively than males.

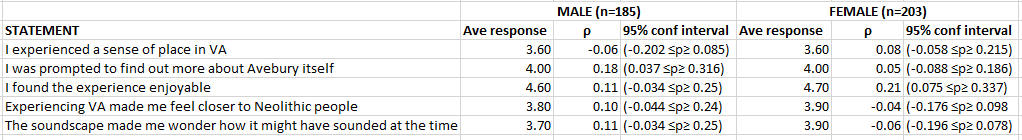

To explore this, Table 1 below shows:

- the average level of agreement with 5 of the statements about experiences in VA (the higher the score the more positive the response, with 2.5 being the fulcrum between positive and negative responses), and

- correlations (ρ) between immersive tendency responses and those 5 statements,

differentiated by gender. And a strange thing emerges. Nothing! Well, not really, but the pattern is more complex than we might expect. Both males and females are in fairly close agreement in their responses to the statements, with both groups agreeing most strongly that they enjoyed the experience and agreeing least strongly that they experienced a sense of place in VA – although they were still in agreement with that statement. The values of the Pearson correlation coefficients (ρ) show little association between the responses to the immersive tendencies question and responses to the statements, although a weak association (>0.1 <0.3) is suggested between immersive tendency and enjoyment of VA in females.

Lots more to do to unpick some of this, not least that there seems to be a little more association between immersive tendency responses in males and their responses to VA, which we might not have expected to see given the above discussion. The stand-out message for me, though, is how little difference there is between male and female responses to VA, which makes me wonder whether males and females answer questions about immersive tendency differently, rather than there being any actual significant difference. I feel another literature review coming on!

REFERENCES

Falconer, L., 2(013). Situated learning in virtual simulations: Researching the authentic dimension in virtual worlds. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 24 (3), 285-300.

Janssen D., Tummel C., Richert A. and Isenhardt I. (2016). Virtual Environments in Higher Education – Immersion as a Key Construct for Learning 4.0. ICELW Conference, June 15th-17th, New York, NY, USA. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6543/769b9fee49639f5a8b4b3e728a7bd3250b71.pdf

Witmer, B.G. & Singer, M.J. (1998). Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 7, 225- 240