In an article published on the front page of the Times on 13 July, entitled “Google pays academics millions for key support”, researchers of Bournemouth University have been accused of not disclosing funds received by Google to support the tech giant’s policy interests. The allegation is based on a report issued by a US group called “Campaign for Accountability” and extensively covered by the Wall Street Journal on 11 July. The report makes various allegations on Google’s financial support for academia and identifies 115 academic papers which were “in some way funded by the company”, but in which the author(s) “failed to disclose funding”. Based on data published in the report, the Times writes:

Maurizio Borghi, a law professor at the University of Bournemouth, received a faculty research award of $US30,000 from Google in 2014. Last year, he published a paper suggesting that volunteers could be used to identify the copyright status of books to be digitised and put online, and track down rights holders where necessary. Google has digitisation projects, such as Google Books, which would benefit from such crowdsourcing, but he did not declare the funding.

He said that the award was not relevant as his specific research was supported by other funders. “It is true that this is a topic in which Google has a material interest, but it is also true that the award has not prevented me from expressing very critical views on Google,” he said.

Nondisclosure of private funds is a serious violation of research ethics. Receiving money to back private interests in academic research is not only against ethics, but is also dishonest behaviour and unequivocal breach of academic integrity.

The facts: 1) the Google Research Award

In August 2014 I was awarded a $ 40,000 Google Faculty Research Award for my research on ‘Enhancing Access to European Books through Crowd-Sourced Diligent Searches’. Contrary to what suggested by the Times, the Award has been publicly declared, both by CIPPM and by Bournemouth University (see the news posts here and here). As explained in the award letter, the Google Research Award is an unrestricted gift given to the University in support of “excellent research” by its faculty. “Unrestricted” means that no conditions are imposed on the use of the money. I autonomously decided to invest the whole sum to match-fund a PhD studentship offered by Bournemouth University, which has been advertised in May 2015 under the title ‘Mass digitization, cultural heritage and the law’.

The facts: 2) the paper on crowdsourcing copyright clearance

In December 2016, I published the article “With Enough Eyeballs All Searches Are Diligent: Mobilizing the Crowd in Copyright Clearance for Mass Digitization” in the Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property. The article is co-authored with Kris Erickson (University of Glasgow) and Marcella Favale. As declared in the first footnote, research for the paper was carried out as part of EnDOW, a 3-years project funded by the EU Joint Programming Initiative in Cultural Heritage and Global Change. The paper and the project address an issue of acknowledged public interest: how to make European cultural heritage more accessible online in full respect of copyright law. It is not a subject of interest “of Google”, and most importantly it is not a research that Google has commissioned, funded, contributed to or even inspired. The authors did not declare the Google Award in the paper for the very simple reason that the Google Award has no relation with the research carried out for this paper. The statement of the Times according to which Maurizio Borghi “did not declare the funding [from Google]” is a wholly misleading representation of the facts.

Comment: the Times and post-truth journalism

The journalist of the Times was well aware of these facts. However, he deliberately manipulated the truth to make up a plausible story about British researchers getting “secret funds” from Google, and to substantiate unproved revelations on bad academic practices (for critical comments on the methodology used in the “Campaign for Accountability” report see here, here and here). The real name of this kind of operation is post-truth journalism: a form of reporting that has no interest for the pursuit of truth, and whose sole purpose is to persuade the public about a pre-determined and pre-established “truth” – namely, “academics are on Google’s payroll!” –, which is frequently functional to interests that are no less material than those it pretends to unveil. We all know that big publishing corporations and tech giants are currently opposed in a fierce battle on market power across the media sector, and it is no mystery that News Corporation (owner of The Times and the Wall Street Journal) is on the frontline of a worldwide battle against Google on the control of online ad revenues (for an unbiased account see the Guardian).

As an academic with an interest in copyright law and regulation, I happen to have informed opinions on issues at stake in this long-lasting battle. So, I expressed criticism to Google when I thought its mass digitization policy led to unregulated informational monopoly (see e.g. chapter 5 of my book Copyright and Mass Digitization), and I supported criticisms on the badly conceived “press publication right” lobbied for by publishing corporations at EU level (see here). None of my opinions is inspired by anything else than by my own independent research. None of the research carried out at CIPPM has any other purpose than advancing knowledge and contributing to better regulation and lawmaking in the public interest.

Maurizio Borghi, Director of CIPPM, 17 July 2017

Documents

>> Front page of The Times, 13 July 2017

>> Award letter from Google, 19 August 2014

>> Email exchange with Mr. Tom Whipple (The Times)

Post scriptum

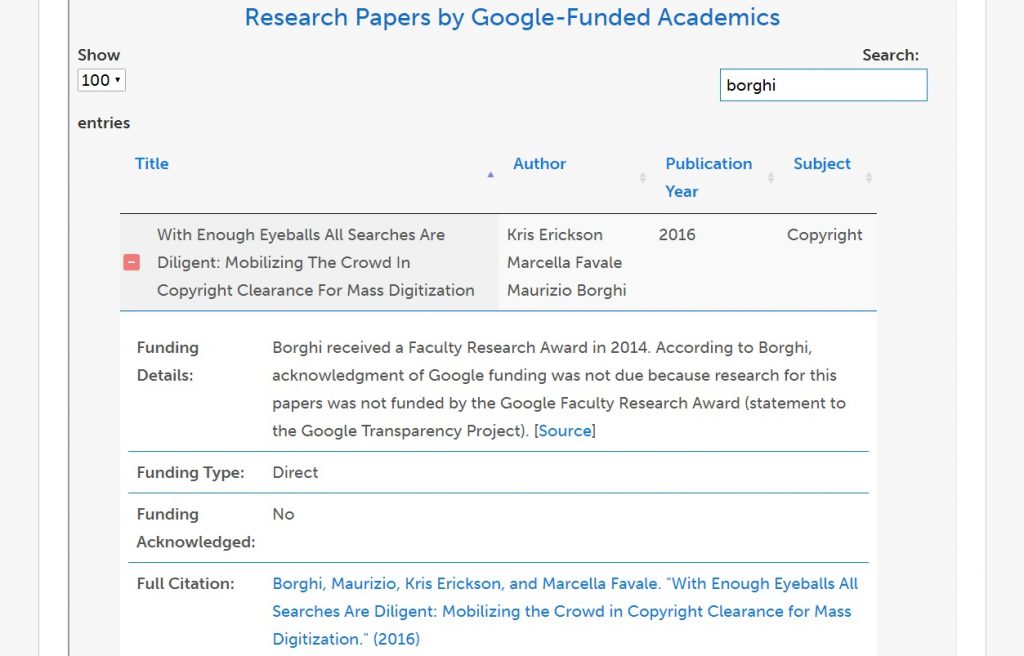

The inclusion of our paper “With Enough Eyeballs…” in the statistics provided by the Campaign of Accountability, according to which out of 330 academic papers “in some way funded” by Google “authors failed to disclose funding … in more than a quarter (26%) of cases”, demonstrates some fallacy in the methodology used by the US group. I asked the group to have the paper removed from their Database of Papers by Google-Funded Academics, or at least to include a disclaimer that the paper is not funded (let alone “directly funded”) by Google. After some email exchanges, the record has been updated as follows: